Whether you live in Calgary or California, chances are you’ve heard of the allure of the noni fruit.

Often incorporated into health-boosting juices and sold as shots throughout Hawaii, some predict that noni may soon rival the ultra-popular acai berry.

Article and graphics by Haleakala EcoTours.

But what, exactly, is this exotic plant, and what’s the story behind it?

Otherwise known as nonu, Indian mulberry, and “cheesefruit,” noni hails from the coffee family and thrives in tropical climates throughout the world. It’s believed to have originated in Southeast Asia and Australia, where the tubular flowers from the evergreen shrub were once consumed raw by Aborigines.

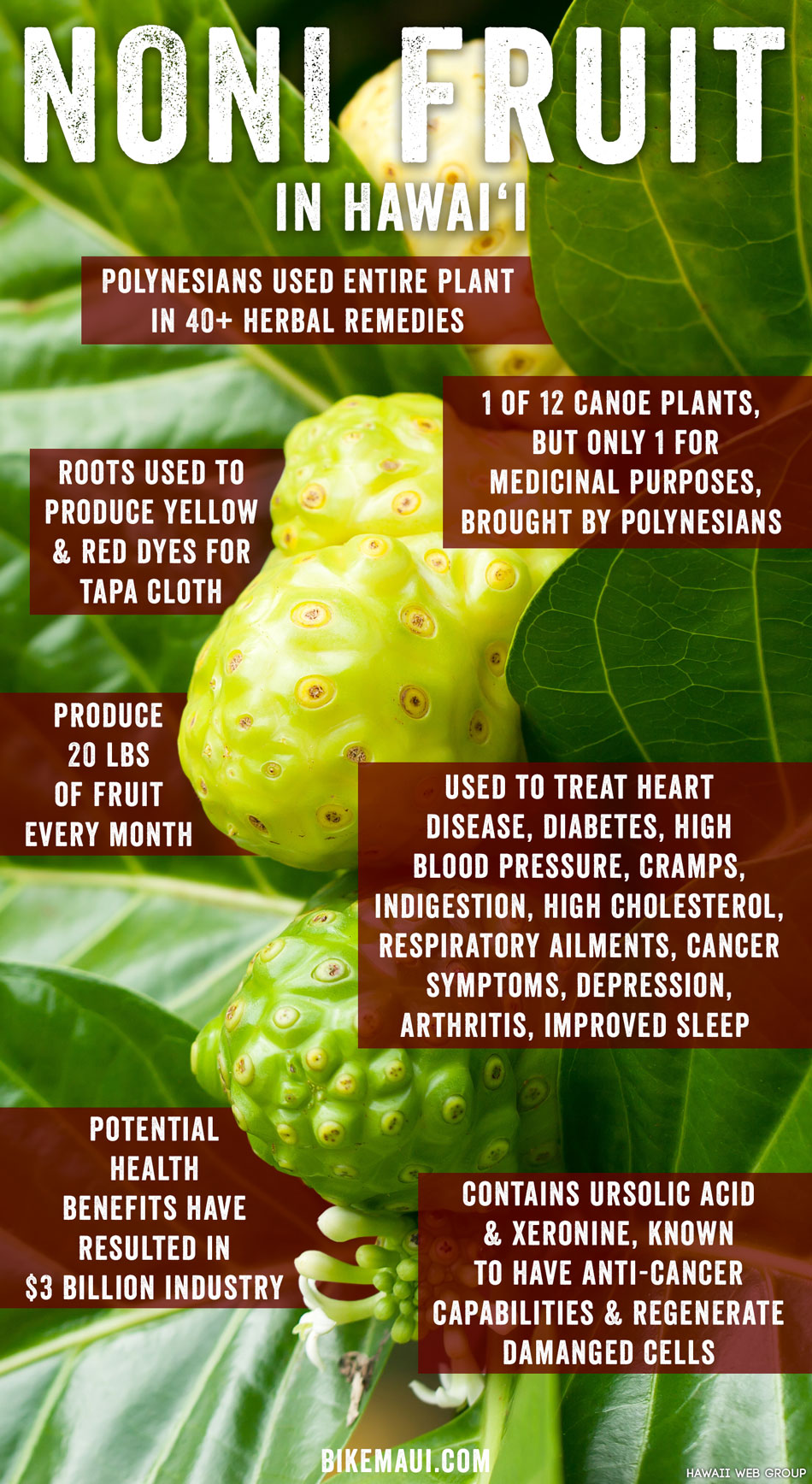

The noni plant—which bears fruit year round—holds a special place in native Hawaiians’ hearts (and explains its ubiquity throughout the islands):

It was one of twelve canoe plants brought by Polynesians to the islands, sharing space with ‘ulu (breadfruit), taro, bananas, bamboo, and kukui, but carrying its own rare power as the only plant carted across the sea for medicinal purposes—and leading to it becoming known as the “queen” of the canoe crops.

Those medicinal purposes were vast and varied.

Notably ingenious with the small amount of resources they brought with them across the ocean, Polynesians used the entirety of the noni plant; records reveal that the bark, leaves, flowers, stems, and roots were employed in more than 40 herbal remedies. Kahuna la’au lapa’aus (Hawaiian herbalists who began training with herbs as young as five) prescribed eating the noni fruit —which some claim tastes like bleu cheese, while others say much worse—for overall health. The fruit and its juices were used to treat what we know today as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, menstrual cramps, indigestion, high cholesterol, and respiratory ailments. Unripe fruit was massaged with salt and utilized in the management of lesions, broken bones, poisonous bites, and burns. Tea from the leaves of the plant—which grows a bright, shiny green—was relied upon to nurse tuberculosis, the symptoms of cancer, depression, and the aches of old age and arthritis.

The uses of noni—which produces up to 20 pounds of fruit per month when mature—wasn’t relegated to the proverbial medicine chest. The roots of Morinda Citrifolia produce yellow and red dyes, which were commonly used to tint the ever-present tapa (or kapa) cloth—a bark cloth used throughout Polynesia for clothing, blankets, artwork, and more. During times of famine, Hawaiians—as well as Samoans, Tongans, and other Polynesians—reached for noni berries, giving rise to its universal moniker as the “starvation fruit” (and perhaps its current status as a wonder food).

But it wasn’t until Elmer Drew Merrill— an acclaimed botanist at Harvard University—wrote the U.S. Military Survival Guide during the second World War that the benefits of noni began to reach the larger populace. Written for soldiers based throughout Polynesia in the Pacific Theater, Merrill recommended that GIs turn to noni in emergencies. In response to the strength it engendered, biochemists began studying its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties.

It was through such research that the Polynesians’ understanding of the incredible plant were proven true—or thereabout (further research remains to be completed).

Studies show that noni contains ursolic acid—a phytochemical, also found in apple peels, blueberries, cranberries, and more, that may have anti-cancer capabilities, as well as xeronine, a vital alkaloid that may regenerate damaged cells. Meanwhile, studies out of Japan have found that noni also possesses damnacanthal, which may have some efficacy against pre-cancerous cells, as well as key components that may provide protection against stroke impairment. Native Hawaiians were also onto something when they used noni to improve sleep—French studies determined that the plant holds sedative qualities. And ancient Ayurvedic texts reveal that noni—deemed “Holy Basil” throughout India—was synonymous with longevity for a reason: Recent research points to noni’s immune-bolstering, tumor-fighting characteristics, as well as its ability to thwart parasitic diseases.

Proponents of noni today are quick to offer tips on its benefits—particularly people of Hawaii, who believe that the noni growing here is, thanks to the dearth of pollution, some of the purest noni on the planet. Some suggest mixing noni with garlic to use as a blood purifier and to bolster the immune system through its detoxification qualities. Others take noni supplements religiously with the hope that it’ll prevent or diminish the symptoms of degenerative diseases. Others still drink fermented noni juice—spiked with grape—to enhance weight loss. Studies on the magical but bitter-tasting plant continue: In recent years, the University of Hawaii obtained a federal grant to begin research on noni as a potential treatment for prostate cancer (with a clinical study presently underway), while the National Cancer Institute is funding preliminary research on the pungent plant for use in breast cancer treatment and prevention. Indeed, the popularity of noni’s powers—potential and otherwise—has resulted in a $3 billion industry; the fruit itself is often seen in juices, supplements, powders, cosmetics, shampoos, and lotions.

With sturdy branches made of coarse wood, noni produces a fruit that’s approximately the size of a potato or small breadfruit and boasts a waxy, lumpy exterior.

Traditionally, Polynesians picked the fruit prior to ripening and stored it in the sunlight until it became edible or primed for medicinal uses, but knew where it was flourishing simply by its off-putting odor. (That smell apparently diminishes once it’s fermented.) And where it prospers is as wide-ranging as its medicinal benefits: Noni is just as likely to thrive in an arid field of lava as it is in brackish tide pools and sodden rainforests.

In other words, noni may be nearly everywhere you turn if you happen to be visiting Maui or the other islands.

Look for its greenish-yellow, bumpy fruit, or stay aware of its notorious odor. And should you find yourself on the North Shore, pop into Paia’s Mana Foods. This gem of a health food store sells Oahu’s Herbologie acclaimed noni leaves. Brew yourself a mug of tea and understand why Polynesians equated this special plant with optimal health and boundless energy.

Photos courtesy of Photographers in Hawaii.

While on a Volunteer on Vacation work day, in the Honokowai Valley on Maui, I was bitten by fire ants. One of the leaders, a very old Hawaiian woman, pick a Noni and put it on the bits. Very shortly the sting was gone.

Actually visited a noni farm on Kauai last year. My husband has beed taking noni for years. We live in CT and have sold a lot of our boomer friends on its many benefits.

These are hard to consume. They taste and smell like vomit mixed with stale urine. I am not capable of consuming it fresh or as a juice, because it makes me vomit. Too bad the taste is so horrible, with such great health benefits. Good luck though!

I have some growing in the backyard. It’s sometimes called “cheese fruit’ for a reason.

Until now I didn’t know the history or health benefits.